In his Eggs, Knives, and Crosses series, Warhol reinvigorated his portrayal of representational forms while simultaneously invoking the compositional principals of abstraction. Created between 1981 and 1982, the silhouetted arrangements of eggs, religious crosses, and kitchen knives emphasize figure-ground relationships, capitalizing on silkscreen’s ability to replicate each representational element, and ultimately bringing the works to the brink of abstraction.

The use of mechanical procedures to simultaneously embrace and eschew abstract expression has been perpetuated by Christopher Wool, who rose to prominence in the 1980s to re-engage with the then- outmoded medium of painting. In the 1990s, the artist began fusing silk-screen techniques with digital technology, photographing forms and marks from his corpus of paintings and digitally altering them using Photoshop, converting them into silk screens, and transferring them anew onto canvases. His original painted gestures were manipulated by a succession of processes that left the artist’s presence undetectable. Akin to the images in Warhol’s Shadows and Rorschachs, the dense splatters, smears, and sinuous traceries in Wool’s works resemble traditional abstract mark-making, largely belying the technical innovations involved in their creation. Wool’s text-based If You (1992) resonates with Warhol’s Eggs, Knives, and Crosses series in the interplay it stages between representation and abstraction. The robust message recalls some of the fervor of Abstract Expressionism while the rigidity of composition communicates a formal sensibility akin to Color Field painting.

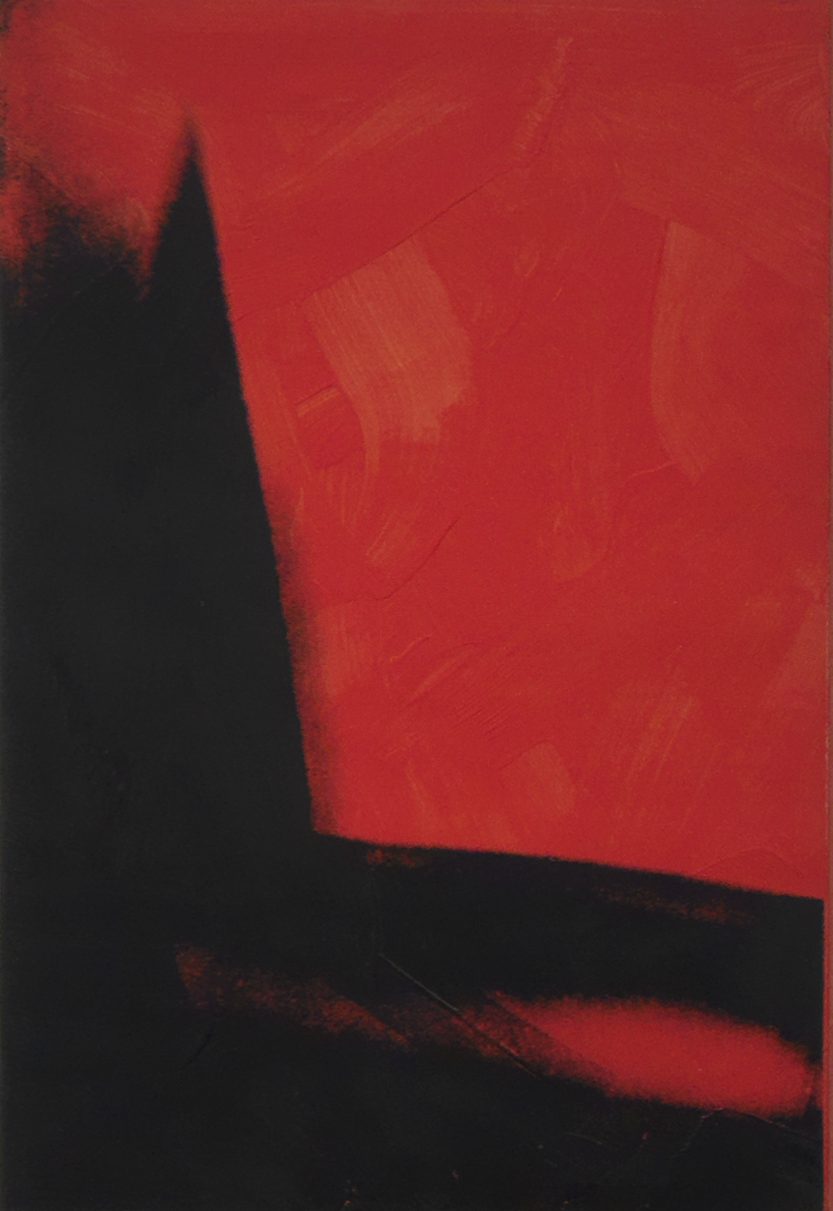

Wade Guyton similarly engages the latest technologies to conjure gestural expression. He digitally creates his compositions using computer programs to select, scan, and manipulate images and letters. The resulting compositions are transferred onto canvas using the artist’s signature Epson inkjet printer. Physically intervening in the mechanics of the printer’s operation, Guyton forces and drags the material through the machine, inducing glitches, blurs, and smears. Despite their computer-aided production, Guyton’s signature works, such as his flame paintings, are redolent with human expression: they embrace errors inherent to the printing mechanism—misaligned registers, fissured edges, drips of ink, and faded discolorations. Harkening back to both Wool’s textual paintings and Warhol’s representational silkscreens, Guyton’s digitally rendered Untitled (2008) depicts overlaid mutations of the letter “X,” resulting in an abstract composition consisting of a repeated figurative element.

The selection of paintings in WARHOL, WOOL, GUYTON traces the trajectory of Warhol’s influence on the work of Wool and Guyton, whose computer-aided printing techniques are a natural progression from the systematic silk-screen process pioneered by their precursor in mid-20th century. The various, highly technical means used by each of the artists yield evocative paintings that oscillate between abstraction and representation.