Foundation News

Jason Rhoades Featured in Forbes

December 13th, 2017

Jason Rhoades at The Brant Foundation Art Study Center, Greenwich, CT

by Clayton Press

Jason Rhoades featured in Clayton Press’s article about The Brant Foundation Art Study Center exhibition.

Even in his absence, Jason Rhoades is still present at The Brant Foundation Art Study Center. It is his pneuma—his subtle vapor, his vital spirit—that permeates this exhibition. Pneuma (πνεῦμα) is an ancient Greek term for a person’s breath that penetrates all things, holding them together. It is this breath, this force that is palpable.

In a 2006 interview, written shortly after Rhoades death, the late Rick Baker, the artist’s former assistant, suggested that Rhoades “never saw the value in cultivating a particular public image . . . [He] regarded the world’s perception of him as an artistic medium itself, like so much paper or clay, to be manipulated just to see what might happen.” The “person”—the self—is core to Rhoades’ work. It is what color was to John McCracken, and what language is to Lawrence Weiner—material and medium.

In Baker’s view, “If someone misunderstood what he [Rhoades] was doing, he found that was as interesting as if they got his intention . . . He would let misconceptions sort of bubble and grow; he was fascinated by the myth that surrounded him.” Was he self-mythologizing like James Lee Byars who made himself into a work of art and who once queried, “My only desire is to explain everything?” Rhoades invariably inserted his life—both fact and fiction—into his installations that function as “concrete,” yet fluid, stories, which in his absence become tableaux.

Like Byars, Rhoades was an adventurer, who might be called a 4-H Club romantic. The 4-H slogan is “Learn by Doing.” Rhoades did. He was “Jason the Mason,” a nickname given to him by his family. After leaving rural Northern California, Rhoades attended the California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco Art Institute (BFA), Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and University of California, Los Angeles (MFA). While he returned home often and used Los Angeles as a command central, he was—like Byars—better known in Europe, where he exhibited regularly. His résumé reads like a Baedeker (a travel guide) of Europe’s art capitals. Where Rhoades went, he constructed installations, continuing to expand his evolving, cohesive build-o-graphy.

The complexity of Rhoades’ installations is exceptional, often consisting of seemingly countless components. Large installations are filled with smaller ones. Smaller ones are composed of groups and units. The installations are artworks within artworks with no detail neglected. It seems like chaos at times, but everything is deliberate and certain to the extent that chaos can be managed. In Rhoades’ world, glues, epoxy, and other materials often help bind the parts together into works.

The artist Paul McCarthy, Rhoades’ former teacher, mentor, friend and sometimes collaborator, said of Rhoades’ work:

There was kind of a fog in it—there was, like, a lot of stuff in it, this pile of stuff. People would sort of stop at the idea that it was about consumerism, or consumption, or American stuff . . .But the pieces were overlaid like communications wires, like a labyrinth that went nowhere. It wasn’t so easy to find your way into it sometimes.

To complicate matters, Rhoades was in command of his work with every presentation, even more so when he was present in his installations as narrator or guide. Curator Ingrid Schaffner, who organized a partial retrospective of Rhoades’ work said, “though documentation exists outside of the art per se, it’s this constant narrative flow that invariably holds Rhoades’ production together . . . like a good storyteller he never ‘told’ an installation the same way twice.”

In a sense, all of Rhoades’ works should be viewed as components of one life-long work that he began at UCLA. There he constructed his work in character, building a complex continuous narrative of interrelated parts. Three installations are central to the Brant exhibition, but accessory pieces—Yellow Fiero (1994); Anchorimpala SS, Alpinimpala SS (1998), and Shelf (Rattlesnake Canyon) with Unpainted Donkey (2003)—help to enlarge the artist’s timeline.

The key works on the ground floor are My Brother/Brancuzi (1995) and The Grand Machine / THEAREOLA (2002). My Brother/Brancuzi was featured at the 1995 Whitney Biennial. It was described—fairly and evocatively—by the art critic, Christopher Knight, as “an explosion in a suburban rec room . . . Home Improvement meets Artistic Engagement.” The installation also paired photographs of the studio of Constantin Brâncuși, the great Paris-based Romanian sculptor, with family album photos of Rhoades’ brother posing at his family’s California homestead. The inventory of materials ranges from stacks of doughnuts à la Brâncuși’s Endless Column to small engines.

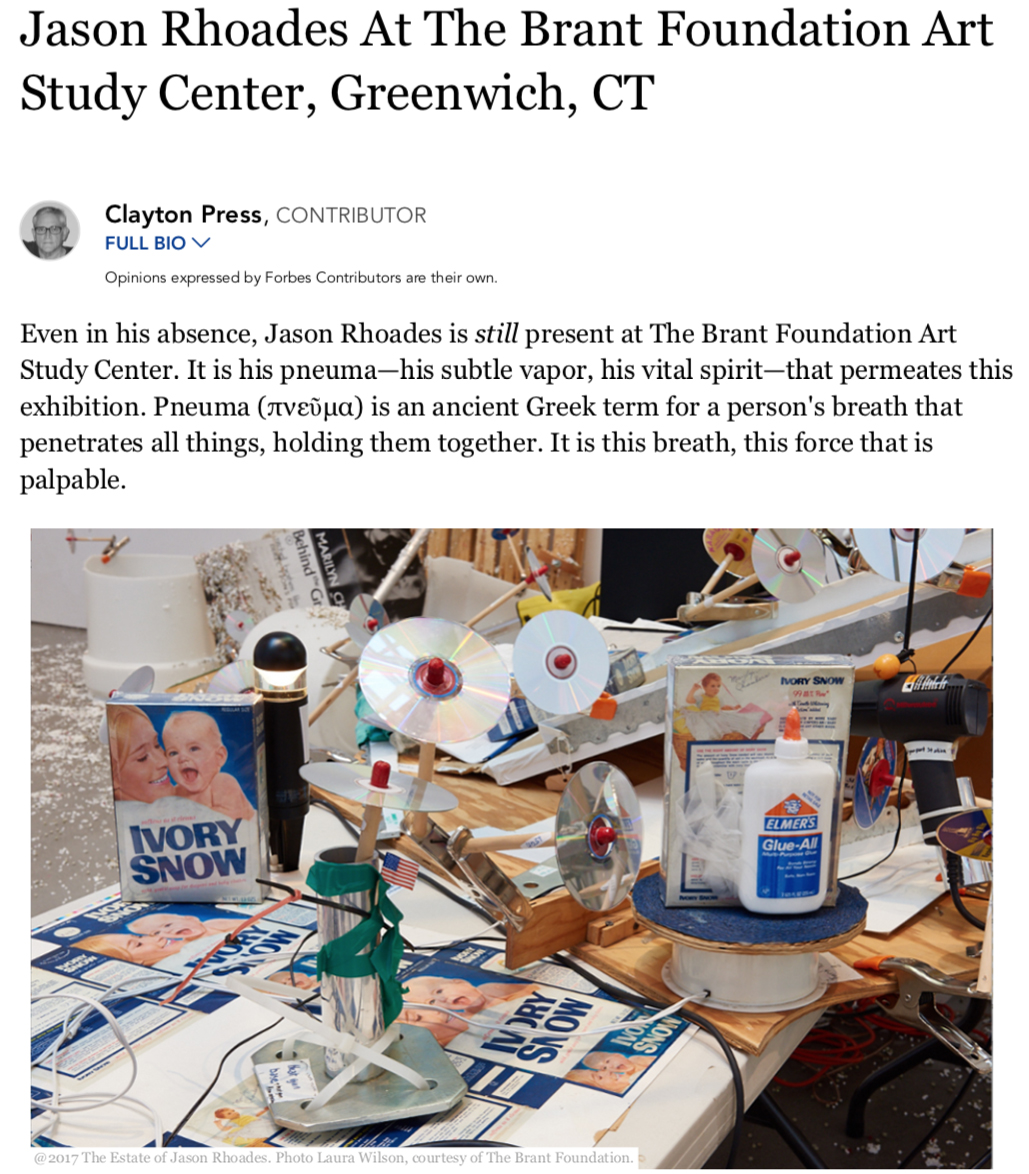

The Grand Machine/THEAREOLA is in fact a factory (with a karaoke studio) for the production of PeaRoeFoam, the artist’s “product.” Here Rhoades’ assistants manufactured do-it-yourself kits that featured Marilyn Chambers, the former “Behind the Green Door” porn star, as the pure, sustenance giving, mother-of-us-all model for the Ivory Snow soapbox—a 99.44% pure Madonna with child in the detergents aisle of American grocery stores circa 1970s. There are multiple allusions to both pornography and mass-consumerism, seriousness and cliché.

Upstairs, there are two important installations. The first is Untitled (from the body of work: My Madinah: In pursuit of my ermtiage…) (2004). This piece was originally presented in its entirety at Sammlung Hauser & Wirth in der Lokremise, St. Gallen, Switzerland. Rhoades had transformed the Lokremise (a train roundhouse) into a partial mosque, partial souq decorated with neon works overhead and recycled towels below, stand-ins for the heavens above and carpets or prayer rugs below. The Brant presentation is a partial, tidy reinterpretation of “My Madinah.” It nonetheless dazzles like a Friday night bazaar in Istanbul, Riyadh or Cairo.

Also upstairs are several works that are clearly related to, although not explicitly part of, Rhoades’ final installation-performance project, Black Pussy Soirée Cabaret Macramé, which was “officially” held in Los Angeles on 10 nights in 2006. It was this final work that Rhoades attempted to tie together the notion of pilgrimage and marketing into a single savvy conflation of “piety and commerce.” Any further description would fail to clarify the complexity of this work. Sadly, Rhoades—the artist, the gatekeeper and the emcee of Black Pussy—died of an accidental drug overdose and heart failure August 1, 2006. Yet throughout The Brant Foundation, and even outside, Rhoades’ pneuma—his subtle vapor, his vital spirit—is present.

Rhoades is quoted as saying, “To juggle the impossible was always an issue throughout my work . . . To take three objects, like a rubber ball, a chain saw and a live African elephant and try to juggle.” His mix-and-match approach to storytelling was not madcap mayhem. It was organized and disciplined, with every detail considered. Schaffner observed, “Look as you might, there is one thing you should never find in the physical and ephemeral work of Jason Rhoades. That is dust. Patently uninterested in the patina of time—dirt was a random distraction drawing attention to a world outside his control—he always kept his installations immaculately clean.”

Since his death, here and there, there have been partial re-presentations of Rhoades’ works, some in galleries like David Zwirner or Hauser & Wirth, and others in non-commercial settings, like the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia. For The Brant Foundation Art Study Center to undertake this exhibition demonstrates its serious commitment to scholarship.

Click here to read the full article.

Jason Rhoades Exhibition at The Brant Foundation Art Study Center, Greenwich, CT