Past Exhibition

- Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol

Greenwich May 12th to October 1st, 2013

ANDY WARHOL

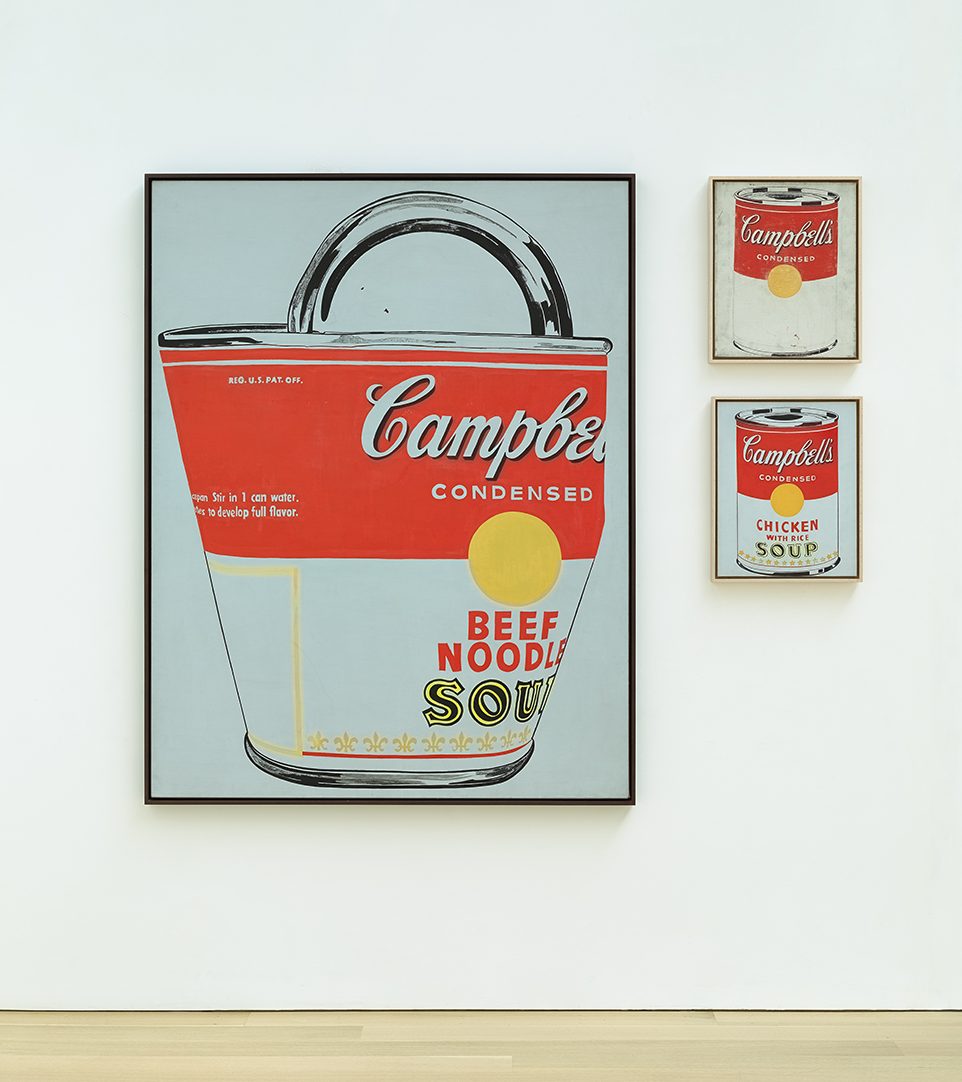

The Brant Foundation Art Study Center is pleased to present the first comprehensive exhibition of important works by Andy Warhol, a homage to one of the most influential artists of the second half of the last century. This exhibition reflects Peter Brant’s lasting passion for Andy Warhol’s work, a rare long-time commitment, which began more than four decades ago. It was Brant who very early in the artist’s career recognized the significance of Warhol’s work, in order to form a truly outstanding coherent collection, never-before-seen in any public institution.

Today, more than 25 years after the artist’s death, we know that Warhol was not only the significant protagonist of ‘Pop culture’, but also one of the most visionary chronologists of his time. In his work we see the resonance of social phenomena: beyond a perfect surface, the mirror of life, in which happiness, death and disaster coincide, in which banality and sophistication meet, in which we see the first messengers of a total media orientated society to come. The spirit of his time could be read like a monologue of an artist observing a society seemingly without emotion. And still, emotion irradiates through the aura of his work.

Programs and Events:

Warhol Exhibition Announcement

Lecture: Andy Warhol: Global Phenomenon

The Brant Foundation Lecture Series: 15 Minutes: Celebrating the Legacy of Andy Warhol

The Brant Foundation Lecture Series: Michael Lobel: Insights about the Warhol Exhibtion

Andy Warhol: Traveling Exhibition

Artist Biography

Andy Warhol

More than twenty years after his death, Andy Warhol remains one of the most influential figures in contemporary art and culture. Warhol’s life and work inspires creative thinkers worldwide thanks to his enduring imagery, his artfully cultivated celebrity, and the ongoing research of dedicated scholars. His impact as an artist is far deeper and greater than his one prescient observation that “everyone will be world famous for fifteen minutes.” His omnivorous curiosity resulted in an enormous body of work that spanned every available medium and most importantly contributed to the collapse of boundaries between high and low culture.

A skilled (analog) social networker, Warhol parlayed his fame, one connection at a time, to the status of a globally recognized brand. Decades before widespread reliance on portable media devices, he documented his daily activities and interactions on his traveling audio tape recorder and beloved Minox 35EL camera. Predating the hyper-personal outlets now provided online, Warhol captured life’s every minute detail in all its messy, ordinary glamour and broadcast it through his work, to a wide and receptive audience.

Read More

The youngest child of three, Andy was born Andrew Warhola on August 6, 1928 in the working-class neighborhood of Oakland, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Stricken at an early age with a rare neurological disorder, the young Andy Warhol found solace and escape in the form of popular celebrity magazines and DC comic books, imagery he would return to years later. Predating the multiple silver wigs and deadpan demeanor of later years, Andy experimented with inventing personae during his college years. He signed greeting cards “André”, and ultimately dropped the “a” from his last name, shortly after moving to New York and following his graduation with a degree in Pictorial Design from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1949.

Work came quickly to Warhol in New York, a city he made his home and studio for the rest of his life. Within a year of arriving, Warhol garnered top assignments as a commercial artist for a variety of clients including Columbia Records, Glamour magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, NBC, Tiffany & Co., Vogue, and others. He also designed fetching window displays for Bonwit Teller and I. Miller department stores. After establishing himself as an acclaimed graphic artist, Warhol turned to painting and drawing in the 1950s, and in 1952 he had his first solo exhibition at the Hugo Gallery, with Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote. As he matured, his paintings incorporated photo-based techniques he developed as a commercial illustrator. The Museum of Modern Art (among others) took notice, and in 1956 the institution included his work in his first group show.

The turbulent 1960s ignited an impressive and wildly prolific time in Warhol’s life. It is this period, extending into the early 1970s, which saw the production of many of Warhol’s most iconic works. Building on the emerging movement of Pop Art, wherein artists used everyday consumer objects as subjects, Warhol started painting readily found, mass-produced objects, drawing on his extensive advertising background. When asked about the impulse to paint Campbell’s soup cans, Warhol replied, “I wanted to paint nothing. I was looking for something that was the essence of nothing, and that was it”. The humble soup cans would soon take their place among the Marilyn Monroes, Dollar Signs,Disasters, and Coca Cola Bottles as essential, exemplary works of contemporary art.

Operating out of a silver-painted and foil-draped studio nicknamed The Factory, located at 231 East 47th Street, (his second studio space to hold that title), Warhol embraced work in film and video. He made his first films with a newly purchased Bolex camera in 1963 and began experimenting with video as early as 1965. Now considered avant-garde cinema classics, Warhol’s early films include Sleep (1963), Blow Job (1964), Empire (1963), and Kiss (1963-64). With sold out screenings in New York, Los Angeles, and Cannes, the split-screen, pseudo documentary Chelsea Girls (1966) brought new attention to Warhol from the film world. Art critic David Bourdon wrote, “word around town was underground cinema had finally found its Sound of Music in Chelsea Girls.” Warhol would make nearly 600 films and nearly 2500 videos. Among these are the 500, 4-minute films that comprise Warhol’s Screen Tests, which feature unflinching portraits of friends, associates and visitors to the Factory, all deemed by Warhol to be in possession of “star quality”.

Despite a brief self-declared retirement from painting following an exhibition of Flowers in Paris, Warhol continued to make sculptures (including the well known screenprinted boxes with the logos of Brillo and Heinz Ketchup) prints, and films. During this time he also expanded his interests into the realm of performance and music, producing the traveling multi-media spectacle, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, with the Velvet Underground and Nico,

In 1968 Warhol suffered a nearly fatal gun-shot wound from aspiring playwright and radical feminist author, Valerie Solanas. The shooting, which occurred in the entrance of the Factory, forever changed Warhol. Some point to the shock of this event as a factor in his further embrace of an increasingly distant persona. The brush with death along with mounting pressure from the Internal Revenue Service (stemming from his critical stance against President Richard Nixon), seem to have prompted Warhol to document his life to an ever more obsessive degree. He would dictate every activity, including noting the most minor expenses, and employ interns and assistants to transcribe the content of what would amount to over 3,400 audio tapes. Portions of these accounts were published posthumously in 1987 asThe Warhol Diaries.

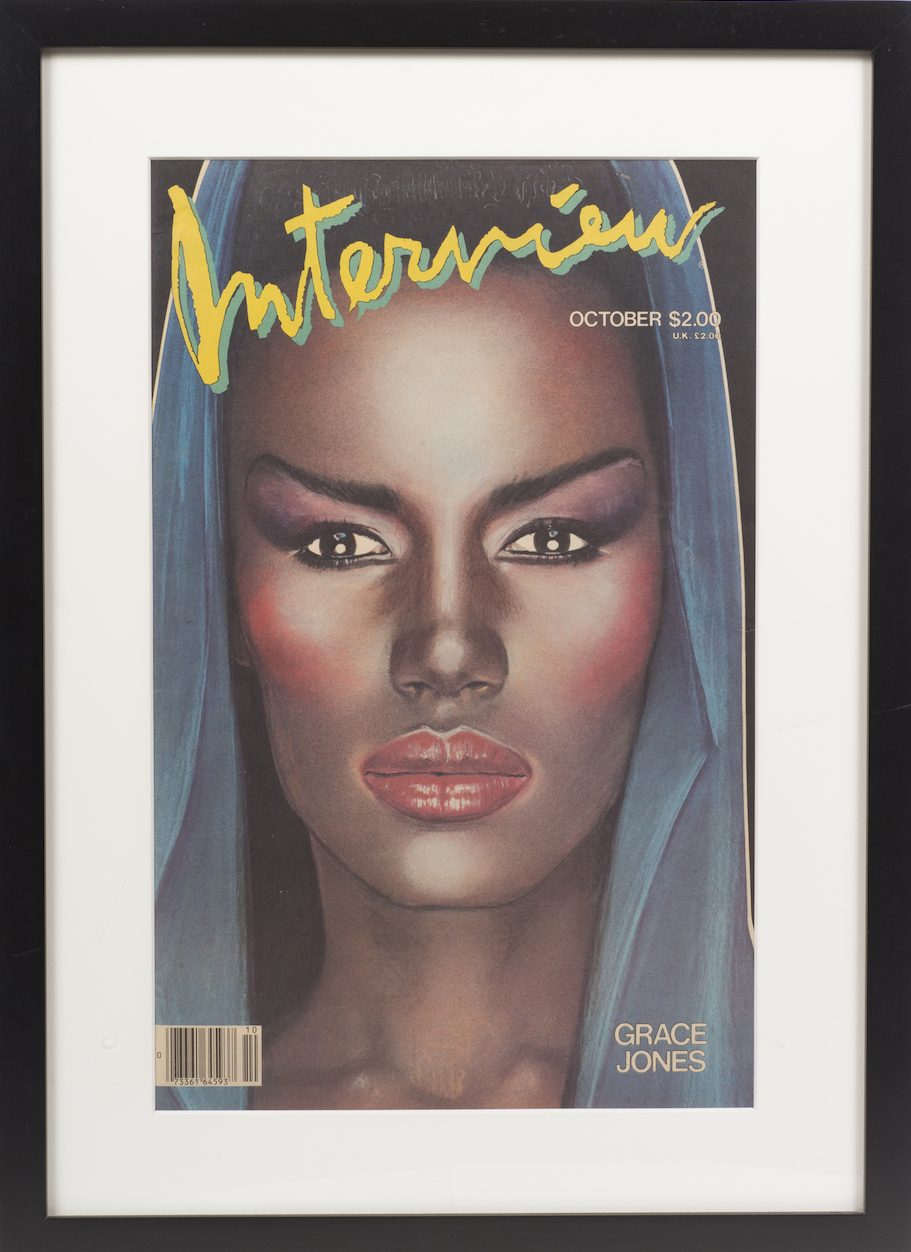

The traumatic attempt on his life did not, however, slow down his output or his cunning ability to seamlessly infiltrate the worlds of fashion, music, media, and celebrity. His artistic practice soon intersected with all aspects of popular culture, in some cases long before it would become truly popular. He co-founded Interview Magazine; appeared on television in a memorable episode of The Love Boat; painted an early computer portrait of singer Debbie Harry; designed Grammy-winning record covers for The Rolling Stones; signed with a modeling agency; contributed short films to Saturday Night Live; and produced Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes and Andy Warhol’s TV, his own television programs for MTV and cable access. He also developed a strong business in commissioned portraits, becoming highly sought after for his brilliantly-colored paintings of politicians, entertainers, sports figures, writers, debutantes and heads of state. His paintings, prints, photographs and drawings of this time include the important series, Skulls, Guns, Camouflage, Mao, and The Last Supper.

While in Milan, attending the opening of the exhibition of The Last Supper paintings, Warhol complained of severe pain in his right side. After delaying a hospital visit, he was eventually convinced by his doctors to check into New York Hospital for gall bladder surgery. On February 22, 1987, while in recovery from this routine operation, Andy Warhol died. Following burial in Pittsburgh, thousands of mourners paid their respects at a memorial service held at Manhattan’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The service was attended by numerous associates and admirers including artists Roy Lichtenstein, Keith Haring, and entertainer Liza Minnelli. Readings were contributed by Yoko Ono and Factory collaborator and close friend, Brigid Berlin.

Plans to house The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh were announced in 1989, two years after the establishment of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Through the ongoing efforts of both of these institutions, Andy Warhol remains not only a fascinating cultural icon, but an inspiration to new generations of artists, curators, filmmakers, designers, and cultural innovators the world over.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The Brant Foundation Library: Selected Resources Inspired by Fashion Week

The Brant Foundation Loan Program: Andy Warhol – Little Electric Chairs

The Brant Foundation Loan Program: Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again

Andy was a person who had an eye for beauty, whether it was a great piece of furniture or a Coke bottle. He saw the best in things.

– Peter Brant

In August '62 I started doing silkscreens. The rubber-stamp method I'd been using to repeat the images suddenly seemed too homemade; I wanted something stronger that gave more of an assembly-line effect. With silkscreening you pick a photograph, blow it up, transfer it in glue onto silk and then roll the ink across it so that the ink goes through the silk and not the glue. That way you get the same image, slightly different each time. It was all so simple - quick and chancy. I was thrilled with it. My first experiments with screens were heads of Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty, and then when Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make screens of her beautiful face - the first Marilyns.

– Andy Warhol from POPism: The Warhol '60s, New York, by Pat Hackett, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980, p.22

The best atmosphere I can think of is film, because it's three-dimensional physically and two-dimensional emotionally.

– Andy Warhol