Foundation News

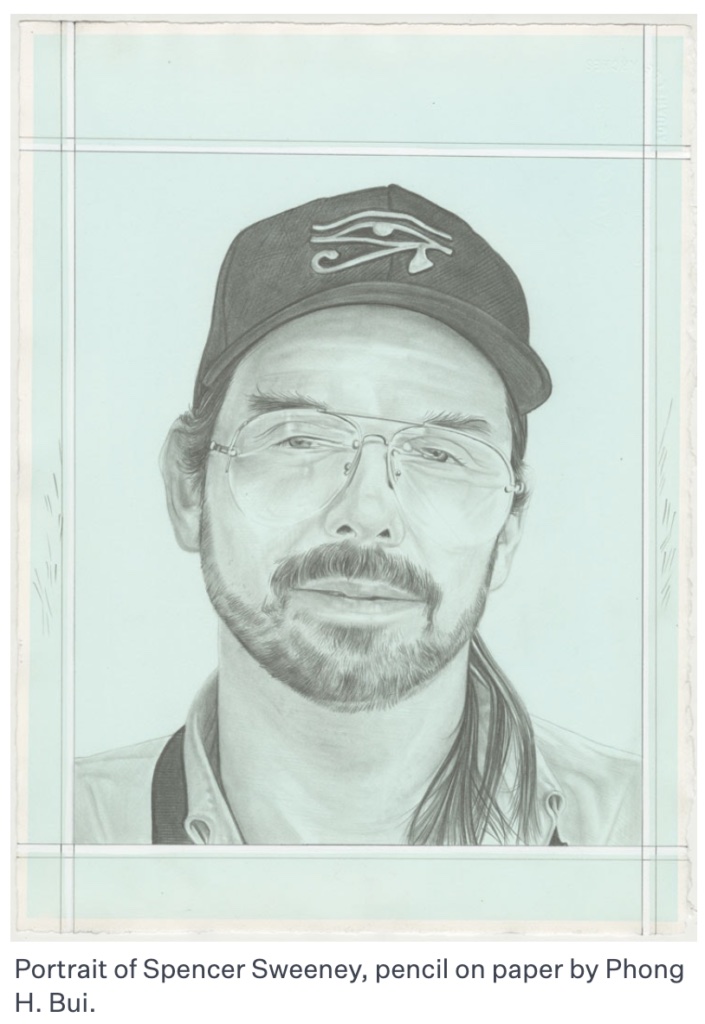

The Brooklyn Rail: Spencer Sweeney with Andrew Woolbright

July 14th, 2022

In early May, Spencer Sweeney’s exhibition Perfect opened at the Brant Foundation. The drawings and paintings that spanned across the two floors of the foundation represented fifteen years of work and achieved the depth and dimension of both a retrospective and a concert . When the energy finally settled from the opening, we talked in his studio, where I found myself surrounded by the same palpable excitement and energy captured at the Brant. Next to his drums and guitars, and flanked by a ring of booming paintings still in progress, we discussed the shared spaces of music and painting, how painting can be used to anticipate and store the energy of an announcement, and how self-portraits can hold the tension of contradictions to emanate and reflect the soul.

Installation view: Spencer Sweeney: Perfect, Brant Foundation, 2022. Courtesy the artist and The Brant Foundation. Photo: Tom Powel imaging.

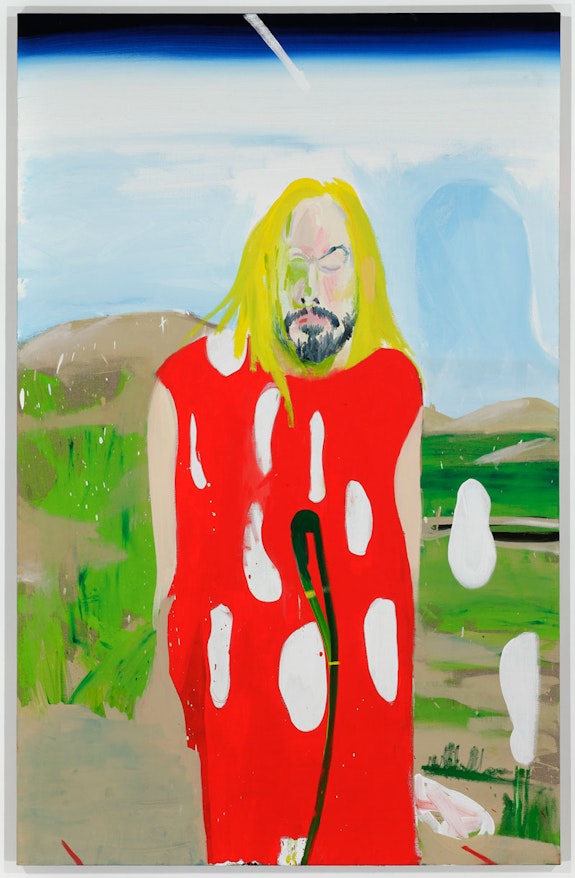

Andrew Woolbright (Rail): You immediately feel this untrammeled energy walking into your show at the Brant Foundation. The first room is a collection of self-portraits. What really struck me is that there is this clarity to the way you’re laying down marks. I felt that you had made your painting practice into your good friend—a friendship of permission where you can just grab something out of the fridge without asking, a familiarity.

Spencer Sweeney: After some time in working with a material one gains a familiarity. This creates an ease with the material. When it comes to articulation through mark making I sometimes find myself thinking of a quote by Miles Davis “It’s the notes you don’t play.” It can be what’s left out that can make the piece or establish the mood or intention. Sometimes when drawing a figure I’ll decide to draw one line, a silhouette, maybe just the neck down to the shoulder, just focusing on the feel of that one line and the object it represents. So the suggestion of that one line can become recognizable as an entire form in all its color and volume. In the self-portraits, the articulation of the figure might be kind of minimal, yet exacting, describing what it’s intending while at the same time almost falling away or apart. For me this becomes a suggestion of the fugitive nature of our corporal existence—we’re here and we’re talking and we’re actually disintegrating as we speak.

Rail: I mean, what comes across too is maybe this love of the first mark, getting it right the first time, but not letting yourself be held hostage by it. You have this freedom to go over something, but an open possibility that that first thing might just be perfect.

Sweeney: Yes, that’s an idea I’m often occupied with. I’ll find myself speaking to other painters about that first mark. You make the first mark, and that’s it. And then if you go over it, retrace it, it’s robbed of its spirit, but you also can’t be too precious with it. You have to be able to obliterate it at any moment—that’s a territory you have to familiarize yourself with. Having the courage to obliterate can lead you into this state of pure motion and creation, where your rhythm and movement become the mark; when you hit this right moment, where every initial move is perfect. It can involve a lot of careful preparation leading to that moment to unlock this wild intuitive movement and expression. So at times painting becomes a balancing act between careful consideration and reckless abandon.

Rail: Can we talk about those portraits? Because they don’t feel like they carry the baggage of artists making the self-portrait, which is typically a kind of masculine, heroic, self-preservation thing. I don’t think your paintings are about establishing themselves as grandiose. I think it’s much more exciting and subversive. I can’t figure out what they are revealing or concealing about you.

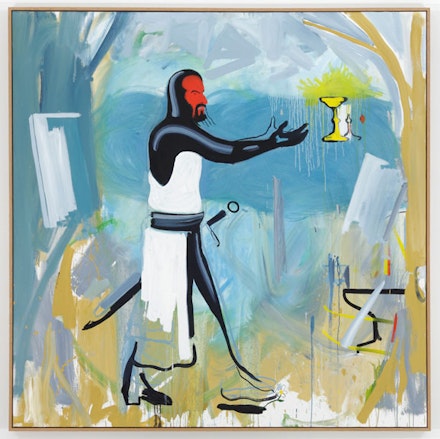

Spencer Sweeney, Grail, 2010. Oil on canvas, 67 x 67 inches. Courtesy Galerie Hans Mayer, Dusseldorf.

Sweeney: Yes there are the moments when the character may reveal more of its nature in its attempt to conceal itself. I mean, that is there, it’s true, but it is also something that appeals to my sense of humor. I deal with the historical narcissism of self-portraiture in some pictures. For instance, there’s the one that depicts this quest for the Holy Grail scenario. It’s poking fun at that idea, of what may be some of the motivations of creating art. Are we seeking some form of immortality or trying to map some unknown territory? That one is an expression of this kind of clumsy ambition, the ultimately destructive nature of the male ego and appetite. Sometimes, there’s this element of self-deprecation. There’s humor but there is also pathos. I need all of those things to feel I’ve served up a somewhat accurate slice of life.

Rail: I like “clumsy ambition.” There is some art historical adjacency in that. I told Phong Bui at the opening, “This is home cooking for painters.”

Sweeney: What do you mean home cooking?

Rail: It just brought up a type of painting that reminds me of what excited me about painting in the first place. It’s familiar but always welcome. Your work has the casual bravura of Kippenberger, or Mike Kelley, or Jonathan Meese. There’s this real energy that’s being brought to the mark but it isn’t being used with the same immolation or contempt that Kippenberger did. You might be tapping into the kitschy-ness of self-importance, or the kitschy-ness of someone taking themselves too seriously.

Sweeney: Yeah, there’s a kind of recognition of the absurdity of the whole thing, of figuring out different ways to depict these absurd disasters of life, [Laughter] or of just being a human being. That comes through in a lot of the scenarios. Sometimes there’ll be little symbols in there, little actions depicted that will be hints to those things. Sometimes it’ll be very obvious, I’ll just decide to go obvious and make a little picture or moment out of it.

Rail: Yeah. I enjoy this very perceivable futility you’re exploring. There’s this unpieced together thing where the body never becomes a full body. There’s accident. There’s play but it’s never frivolous. It’s really virtuosic.

Sweeney: Right, and that’s when I find that the work clicks, and that only comes about when I’m in a state where preciousness does not enter the picture whatsoever. That’s when I come up with the work that excites me. Sometimes you have to work yourself into a state of removal to get away from that. A lot of times, it just has to do with rigor; and just being involved in the process so often that preciousness just flies out the window. Maybe it’s like how an athlete trains. It’s really got to become second or first nature to come forth.

Rail: Can you talk more about working yourself into that state?

Sweeney: I remember when I was young going to the theater to watch Straight, No Chaser, the documentary on Thelonious Monk. I remember watching this footage of him on stage next to his piano just doing this particular movement (stomping in small circles). And as a young kid was mystified by this movement. It just struck me. What could possibly be going on there? I went to see the film several times in the theater. Eventually I understood that sometimes you might use a motion like this in repetition to reach this state. Where this movement becomes your entry point to improvisation, creating, and handling something new.

If you’re playing music, to really get to the point where you are tuned into the immediacy of improvisation, there’s something that I can do where I start repeatedly shaking my head to the rhythm. Somehow that puts me in a point where it’s all available to me. I’m sure it has something in common with being in a trance state.

Rail: Oftentimes, the head, like you said, isn’t representational, but it’s specific, and it gets at some type of understanding of yourself through memory or a quick reflection in the mirror. The bodies gave me the sense of marionettes, or piñatas. There’s a flatness to them or a hang, like they are held up by the joints or hollowed out. But maybe that’s picking up on the fugitive nature of living that you talked about.

Sweeney: Right. Or like falling apart, the body is more slight in construction and articulation than the face. With some of those portraits it’s the expression of the face, which becomes the emotional anchor and the thing that emanates from the painting. And then often the body will be rendered sparsely to give it this idea of motion or disintegration or being poorly constructed, being stilted up. But that’s just something that I play with. But the face is often where the power is, you know?

Rail: I like that idea of the face being the emanation point, an origination of self-engineering, like the body kind of engineers itself from the expression of the face; spreading out, like the gesture follows the eyes, the nose, the smile.

Spencer Sweeney, Self-Portrait, 2010. Oil on linen, 66 x 42 inches. Courtesy the collection of Julian Schnabel.

Sweeney: Right, sometimes I get into a certain movement in mark making starting at the face and working out to the rest of the body from there. Where the rest of the body becomes a kind of riffing off the shapes and quality of the mark making I used to create the face.

Rail: Well, it reminds me of how Mike Kelley oftentimes just wanted to talk about representational painting as his reaction to Hofmann’s push-pull. That is just like he said, like, if you saw a face it was more about establishing figure ground, like a type of sign painting or set painting where it communicates the idea quickly to charge it up, so it’s an abstract method applied to making recognizable things and the speed and the movement are the thing.

I feel like a lot of interviews with you quickly expand into this social dimension, like your practice is always bringing in the outside world, through the community that you’re a part of. The Headz improvisational music and painting parties held at your studio and all these different social textures that you’re involved in get brought up a lot. I’d be interested to hear you talk about hosting, or what it’s like being the host of the party, and if you feel that that has a relationship to your practice.

Sweeney: Well as far as the painting practice goes, sometimes it spills out when I am painting a picture in order to announce an event, and it is also a painting outside of that. I remember what instigated my move to New York City—it had to do with a personal discovery of the creative community here. I used to work at a video store and they had this performance art video tape which had a segment of a John Giorno performance, it might have been his Poetry Systems release, and he was doing his thing at a nightclub-looking space. He had the delay on the microphone, and he was just going off, and I remember that the people around him were just hanging off his every word, and just looking at him with this sense of adoration. Watching this performance in situ really had an impact on me.

Here is this community of people who are so animated and enthusiastic about this really wild poetry performance. I think that’s pretty much when I decided to move to New York City. I thought to myself, I have to be where that is. [Laughter] So I packed a bag and Peter Panned it up here.

It made me realize this social element to a creative community is fundamental to its own survival and growth. That’s how ideas germinate and that’s how the work progresses. I was thinking about it in terms of Dada, which had a real social movement to it as well with Cabaret Voltaire. So I found myself putting together evenings surrounding some kind of an action or performance, and I was doing them at Gavin Brown’s gallery on 15th Street at first.

Rail: I always tell my students that art is incredibly social, maybe the most social thing. Maybe there’s a difference between being an artist and a maker—while a maker toils away in their studio, the artist does that while also going to their friends’ shows and showing up for them. New York is the first place I’ve ever lived where artists really help each other and care about each other in a way that feels very real. I’m not saying there aren’t incredibly competitive or professionalized people here; but New York is the first place I’ve ever lived that intentionally tries to connect you to other people for the sake of knowing what creative people getting together are able to do.

Sweeney: Definitely. And I remember a moment when I was considering moving from Philadelphia to New York. I was friends with an artist up here named Maura Jasper. And she was filming people singing karaoke for this one project, which was really great in my opinion. So she invited me to come up and be filmed singing karaoke. I chose to sing John Lennon’s “Mind Games” while brushing my teeth. So I did that thing and afterwards I thought “Might move up here.” And she was like, “Well, you definitely should. There’s a really great community of very cool, supportive people.” That was very much in contrast to what I was hearing back at art school in Philadelphia. When I mentioned moving to New York, it was like, “Good luck kid. You’re gonna be a goldfish in a shark tank.” And then Maura was like“No, actually, that’s just wrong.”

Rail: It really is. I mean, it’s funny how the outside perspective is so radically different than the reality.

Sweeney: It is radically different, but I’m still curious about your question about hosting. Would you expand upon that a little bit?

Rail: So the host I think always kind of withdraws or subtracts themself in some ways in service of the party. Like the host typically is the last person to eat. Sometimes the host never has a drink because they’re so invested in making sure everyone’s having a good time. I was reading an interview you gave with Andrew W.K., where you said, “I’m always worried that people will look at my portraits as narcissistic or megalomaniacal,” and I never once had that moment where I thought that.

Sweeney: Well, that was at the onset of the series. And afterwards I was still fucking mortified to be in that room. But I’ve kind of had to let that go.

Rail: I never interpreted them as narcissistic, which feels significant. They felt to me like things that are made after the party’s over, after everyone’s passed out in the living room on the couch. There’s this feeling with the self-portraits of trying to find yourself again after the dissociative feeling of an all-nighter. There’s a lingering energy from the social events, but the paintings feel like they are a step removed, an action of recentering or reconfiguring yourself away from the group, in a different room from everyone else.

Sweeney: I’m not actually sure if I can relate to that. But, there is this kind of dichotomy in the self-portraits where it’s a celebration and it’s also a criticism happening at the same time. So in a way it becomes a celebration of the imperfections and challenges and the disasters of life as it happens.

Installation view: Spencer Sweeney: Perfect, Brant Foundation, 2022. Courtesy the artist and The Brant Foundation. Photo: Tom Powel imaging.

Rail: Can you talk about the impetus or what was behind the next room, the monumentally-scaled reclining figures? That seemed very different tonally.

Sweeney: Yeah, well it’s certainly a different experience than the self-portraits. I decided to start painting these feminine beings. At the time, things were feeling very bad boy, you know, the art conversation felt that way at the time. In a sense these paintings were somewhat of a reaction to a surrounding mood. I felt motivated to bring these feminine characteristics and qualities into the world, not even knowing if they would ever become part of any conversation or not, but that was just what occurred to me at the time.

I also saw this as a way of exploring my own feminine characteristics, so I started on pictures and at one point, I thought, “Well, what if they were to expand and become more of fields?” And I started thinking of them more as fields of energy and in terms of creation, and the universal expansion and creation of life. And I wondered if these paintings could act as more than something you engage with on a pictorial level, and represent more of an energy field, something that you’re more surrounded by than focusing in on. And so they became these environment-sized feminine forms, and it was what was going through my mind at the same time. There’s also something to the creative force of the universe that I had identified as being primarily feminine.

Rail: I like the way you describe them, as actions that hold the tension between how you’re perceived and what you want to be able to accomodate. And they are fields, like you said. Paintings like Guernica use scale to impress the responsibility of remembering onto the viewer. The way you’re painting the recliners, they feel intended to function as a backdrop to action and social activity, like they are landscapes behind an audience talking to each other.

Sweeney: I like this idea of a backdrop that brings things to life! I also think of them as depictions of the universe. It makes me think of this great Krishna painting that depicts the universe as a running figure, with all the different qualities of the physical realm coming together to create this running figure who’s like looking at you like, “Who the fuck are you?” I love how lavishly illustrated it is. Hinduism has the farthest reaching religious philosophy that I’ve ever come in contact with. So I started thinking in terms of that kind of expansion. Of having an energy field that’s also illustrated through a body in action, or, in that case, almost inaction, because they’re reclining figures. Even when you’re resting you’re still participating in universal expansion.

Rail: Maybe that gets at Hinduism’s scale and ability to record time?

Sweeney: That’s fascinating. So those forms became like the process of expansion, suggested by scale. You find yourself more within a field of color, or energy, rather than narrowing your focus to look at a picture that’s smaller than you. We’re all part of this field, an expanding field which we ourselves make up as being particles within and sharing particles throughout, all doing our part. Maybe that’s a community. When you were talking about hosting and painting, let’s just say when you paint, you’re doing so to communicate with a group of people, and that might be an expression of the soul. There is some kind of inexplicable reality and magic where every being has their own unique voice. So literally when you think about soul singing, Ray Charles has a different voice from Stevie Wonder, both entirely complete and completely unique. And so everyone’s just kind of waiting around to hear the expression of each other’s soul, that’s the audience. And when it’s able to come through, when it is clearly an expression of that, everybody gets excited.

Rail: I think that’s why I keep thinking of hosting in relationship to your work. It’s maintaining the energy for everyone. There’s an electric charge to that first idea, best idea—that first mark. Balancing confidence and pathos with humor and bathos and searching for what gets elevated and what fails.

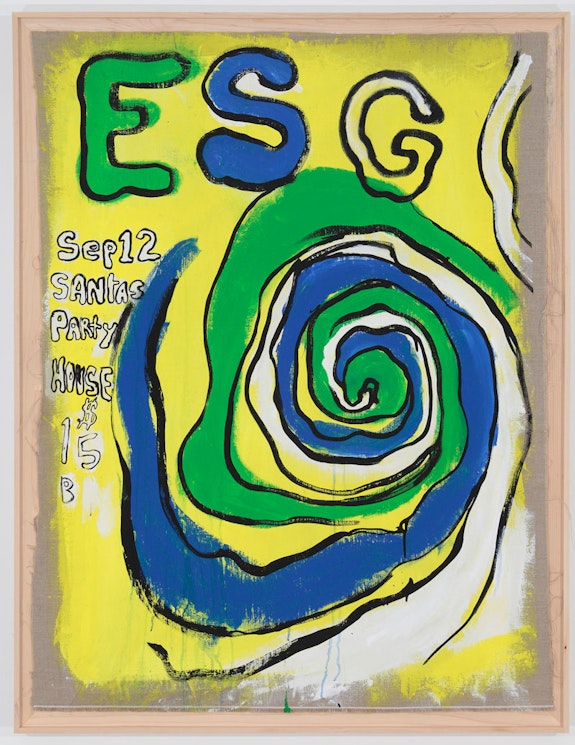

The upstairs at the Brant is all of the show posters. I keep thinking about how much they must have been able to prime the person who saw them to be ready for the party. The way they’re painted kind of prepares you—it works you into a state, visually, that you can project yourself into the feeling of the party.

Spencer Sweeney, Party Painting, 2011. Oil on linen, 51 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Sweeney: Well, yeah. I think that’s just the case of—you’re trying to get the energy across of what you’re announcing.

Rail: Yeah. But you do it so effectively. I mean each one of those posters has a charge to them that prepares you for the type of—

Sweeney: Yes it becomes an exercise in visually interpreting and transmitting the energy of the given event. One aspect that would excite me about doing those paintings was inducing this almost mystical ritual head space; this deep level of concentration while composing. It’s like chanting the name of something that you believe very deeply believe in, like ESG—okay I have to paint the letters “E,” “S,” and “G,” and I get to repeat the magical words “Emerald, Sapphire, and Gold… Emerald, Sapphire, and Gold!” I really enjoyed creating those moments for myself. I mean why not?” [Laughs]

Rail: That’s awesome. I love that.

Sweeney: Then you can get kind of lost in this almost religious mystical rapture, you know [Laughter] cause here you are painting it and they’re going to be playing and performing and one of their daughters will be playing the bass! And wow this is it! So in that grand gallery you have a collection of all these moments chronicled in paintings, there’s a lot of energy transmitted from that, when you look at them and when you can consider the quality of the artists and the experience of their performance. That’s what the experience becomes.

Rail: Yeah. Do you think that there is that same energy carried over into the reclining figures and the portraits, or do you view them as a separate—

Sweeney: Although the bodies of work have significant differences, I do feel there is a certain energetic continuum, maybe in the qualities and approach to transmission of the ideas. Probably some identifiable similarities in mark making as well from one picture to another. I see a continuum.

Rail: For me it kind of feels like there’s a similar speed of committing to the idea while it’s still fresh in your mind; telling people about the party quickly. So there’s an energy there and in the portraits and the reclining figures of getting it down and covering the surface quickly before you lose it.

Sweeney: Right. And so often the challenge becomes: how do I transmit this feeling of this initial idea and expression—that energy of immediacy—into an inert material. I’m always working with that idea, how do you maintain the energy and the vitality of that idea?

Rail: I also like that it remembers and stores a different kind of time. It’s like the difference between history paintings and murals, how the first communicates events and the second communicates everything else—the community, the families, the day to day life of the neighborhood. It’s done with a speed and a directness that’s meant to be remembered, simple shapes and flat colors that allow you remember the mural long after you see it, and enables you to picture it in your mind. I like how these posters store the energy of parties. You even get a sense of the artists who were there, the music—a history of parties and communities.

Sweeney: Well there is also the factor that we all have a finite amount of time to do what we are going to do. [Laughs] But it’s not just that I have to do it in a certain amount of time, but I also want it to embody the energy of the movement. So how do you articulate that movement through these materials? And then it can become movement based in that sense. Where the quality and speed of your movement dictates the expression of the mark.

Rail: I was reading something where someone started talking about Jonathan Meese and saying that he used humor to reveal cultural violence. I feel like you use humor, but in a different way. I don’t think it’s about unearthing historical violence, but I do think that humor is an entry point into something else.

Sweeney: Let’s see. It’s that humor and tragedy are happening simultaneously, inevitably, in the world. So often humor is there sharing the room with disaster. I mean sometimes it could be a somewhat playful observation or even celebration of whatever disasters one may be experiencing in life or intimately during your own creative process. That is often an interesting point of convergence of circumstance for me, and becomes what I set out to express. So the expression is to me somewhat related to the comedy and tragedy persona archetype.

Rail: So it’s more of a counterbalance to deal with the intensity of tragedy. How do you feel personally when you get that stuff out?

Sweeney: Sometimes to prepare myself for painting a self-portrait, I put myself into a very morose, almost depressed state. I think it might be somewhat of a defensive move. So I’m not going to get caught up and become hyper-critical of my own performance. Because it’s really just small beans, in relation to… [Laughs] to the inevitably destructive forces of the universe.

Rail: That’s brilliant.

Sweeney: But then sometimes the resultant picture may turn out rather humorous, or a light-hearted gesture, you know? But that’s not where I started. Sometimes I think about, for instance, maybe a really great comedian. The end product can be a celebration of humor and an expression of light, but it can be pure torture to bring it out. [Laughs]

Rail: Completely. I was thinking as you were talking of the maxim that comedians are usually the most depressed people, because the person that wants to go into comedy, they externalize—they want other people to feel what they can’t. So it projects a feeling they have trouble with through others.

Sweeney: Well, then there’s the idea for the title of the show. I called it “Perfect” because it isn’t and nothing is and therefore everything may as well be. But anyway when this idea came about people were telling me not to call it that. When I first discussed the idea with friends their immediate reactions would be to come up with alternative names. [Laughter]. And so the way I was thinking about Perfect, again, was some kind of celebration of personal disasters—the challenges and the misery that come along with the creative process. Actually, at the end of the day, it’s all perfect. So I kind of equate that to this very challenging Buddhist philosophy: at the end of the day, as miserable and painful as your life may be, it’s all perfect. Everything about the universe is. Again one of the most challenging ideas out there. So somehow it all made sense to me. A lot of these paintings are about the actual act of painting and the creative process. So with all of its pains and challenges, at the end of the day you’ve expressed yourself, and it’s all just perfect.

Rail: Therapy is learning to accept what you can’t control and coming to terms with how little we are regarded. Reality is relentlessly immutable. Perfect.

Sweeney: And as tragic and painful as the whole shared experience of the world might be, who are we to say that it’s not perfect on a scale much larger than the human experience. It’s an extremely challenging idea.

Rail: How do you feel after you’re done making them?

Sweeney: It can happen in a number of ways. Sometimes I’m excited by what I’ve done, and I’m like wow that’s a good moment. Other times I’ll be actually just filled with anguish. I’ll be literally nauseated by what I just made. Those often end up being the best paintings. At the moment when they’ve come to life, I can’t look at them. I’ll leave the room gagging or something. And then those end up being the really good ones, often.

Rail: Pastiche is an important instigator throughout the show. The reclining nudes feel like you’re sampling Matisse. The portraits room is a kind of magic lantern, all different types of ways of being, different ideas of the self-portrait and different styles and different periods of history. I don’t interpret that as a kind of postmodern game or even a historical deconstruction. I guess what I’m asking is, what do you feel committed to within these paintings? There are moments of playful irony, but there are also moments where it’s more of a rotation of different styles, maybe for the sake of being able to do it.

Sweeney: I have to embrace irony. Somebody at a party once asked me if I thought irony was dead. “Not at all, irony is a very important device.” It will always have its place.

Rail: Irony is an incredible volume dial. But the way Kippenberger employed it makes us feel like none of us are on the inside of the joke. Maybe he even isn’t. There’s the strategy of disidentification, that José Esteban Muñoz articulates, of historically marginalized communities adopting styles and periods as forms of resistance or survival. You’re utilizing irony in a different way. So I guess my last question is, what do you feel committed to?

Sweeney: My practice is some kind of strange obsession and I actually cannot stop. So I just wanted to identify that. But also, just like with soul music, I’m looking for an expression of the soul. And that’s what I’m looking for from my fellow human beings. That’s what I’m hoping to hear, to see.

Rail: And it’s a really honest interpretation of that. There are days of feeling heroic pathos and days of self-deprecating bathos and tragedy. In every self-portrait you’re dealing with yourself on different terms.

Sweeney: Yeah. And, like you said, I’m happy if there is an element of this functioning as an invitation, as self-expression within a larger collective experience. You can look at the self-portrait as everybody’s self-portrait. It’s a portrait of the humanity of it all. And so maybe that’s where the generosity idea comes from. Some people have described my work as being generous. I don’t think I completely understand that, but I’ll take it.

Rail: It’s an entry point. Your self-portrait is an endless palimpsest or anagram. The person you paint one day is different the next day and blended together with the people who view it; and it’s the ability to become what people need you to be in that moment.

Sweeney: Right, right. A palimpsest with a collective function is an interesting way of looking at it. Another way of expanding one’s personal creative expression into a collective experience might be to start something like a painter’s group or movement. All you need is a good acronym. More soon on that.

Contributor

Andrew Paul Woolbright

Andrew Paul Woolbright is an artist, writer, curator, and educator living and working in Brooklyn, NY. Woolbright is an MFA graduate from the Rhode Island School of Design in painting and is currently a resident at the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program Residency in DUMBO.